|

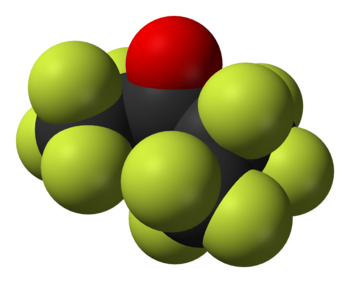

| Space-filling model of the Novec 1230 molecule, dodecafluoro-2-methylpentane-3-one, C 6 F 12 O. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| English: (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

-----

BY ERIC PFANNER

TOKYO – Dropping a home computer into a vat of liquid would wreck it.

Yet some operators of supercomputers are submerging their machines in liquids, without causing any apparent damage, to keep them from overheating. Advocates say submersion cooling could solve one of the biggest challenges of the digital economy: reducing the air-conditioning bills and environmental strains of the power-hungry servers and supercomputers that crunch ever-rising mountains of data.

A prototype supercomputer at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, which is submerged in a tank of mineral oil, has been named in an industry ranking, the Green 500, as the most energy-efficient machine of its kind. The computer, called Tsubame KFC, is 50 percent more powerful than an older supercomputer there but uses the same amount of energy.

“The university administration said, ‘You’re not going to get any more power,’” said Satoshi Matsuoka, the project leader. “But we still wanted more performance.”

Japan is driven to reduce electricity consumption since the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami that caused a meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant. The country idled other nuclear facilities, cutting electricity generating capacity sharply.

The use of liquids to cool supercomputers and powerful servers is not limited to Japan. The technology used by the Tokyo institute was developed by a company in Austin, Texas called Green Revolution Cooling.

Iceotope, a start-up based in Sheffield, England, submerges computers in liquid fluoroplastic, rather than oil. And in Hong Kong, Allied Control, a company that designs cooling systems, used submersion technology for a recently opened data center.

Unlike water, mineral oil and liquid fluoroplastics do not conduct electricity. Therefore, experts says, there is no risk of short-circuiting the equipment.

Peter Hopton, chief executive of Iceotope, said data centers that use air-conditioning could cut their energy bills and infrastructure costs in half by using submersive cooling.

“We’re talking about millions in savings, every year,” he said.

Some supercomputers consume tens of millions of dollars’ worth of energy annually, while the biggest corporate data centers have electricity bills of hundreds of millions of dollars, much of that going for air-conditioning.

Water is used widely as a coolant, but usually it is piped through the facilities or the machines.

Cray, the American supercomputer maker, used submersion cooling for one of its machines in the 1980s. But the method was not widely used, in part because of concern about the high cost and the ozone-depleting effects of the coolants of that era.

Iceotope and the Hong Kong system use new fluids, including one from 3M called Novec 1230.3M says it is not ozone-depleting and has been exempted from the list of volatile organic compounds issued by the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

Mr.Hopton said Novec provided more cooling power than mineral oil.

But Christiaan Best, chief executive of Green Revolution, said that mineral oil was almost as effective and considerably less expensive. Novec 1230, which is more commonly used in sophisticated fire extinguishing equipment, costs about seven times more than mineral oil, he said.

To test viability of its new system, the Tokyo institute erected a small building to house Tsubame KFC just outside a larger lab that contains an existing heat-producing supercomputer. That will give the academics a chance to determine whether Tsubame KFC can function even when the oil warms up to summertime temperatures. They think it might be possible because modern semiconductors can operate at higher temperatures, Professor Matsuoka said.

Only a few modification were necessary to enable Tsubame KFC to be submerged, he said. Moving parts like hard drives and fans to be removed, for example.

Green Revolution’s mineral oil cooling method has been used at several data centers, including facilities operated by the United States Department of Defense. Intel conducted a study of the system and found that its servers had suffered no adverse effects, and power consumption was cut sharply.

Mr. Best said that so far, academic institutions that operate supercomputers had been more willing to experiment with the technology than the than the corporations that run data centers.

“You can imagine,” he said, “if we walk in and say, ‘Why don’t you take your data center and put it in oil,’ you have to have something pretty solid to point to.”

Taken from TODAY, Saturday Edition, March 8, 2014